Business Strategy

On August 26, 2019 in peopleware • 14 minutes readTable of Contents

My notes from the excellent Business Strategy class1 from Coursera.

Leading Strategically

This idea of aligning internal aspects of an organization with the external environment is a core idea in strategy, called strategic fit.

The central insight is that finding a good strategic fit between a company’s organization – its values, capabilities, systems, etc. – and its external environment is critical to ensuring the performance and long run success of the company.

Business Modelling

To understand how aligned a company’s internal and external environment are, we can use a number of Business Model frameworks, high level representations of the core elements of a business, which are useful to understand how will an enterprise create and realize value.

Internal Modelling

Two frameworks for the modelling of the internals of a company aim at expressing its culture and its business proposition.

Mission, Vision & Values

A company’s mission, vision and values set the stage for the correct deployment of a strategy. They must be well thought, true reflection of the company by being lived, practiced and reinforced within the company by its leadership and employees.

Mission

A company’s mission is a brief statement about what the company’s ultimate goals and objectives are; in short, what is its purpose in the world?

Missions are important for three main reasons:

-

It makes transparent to all stakeholders – customers, investors, employees, or business partners – why the company exists and what it is trying to achieve, so they can more easily work together to achieve those goals.

-

Second, because there is this common understanding, it becomes easier to resolve disputes about the future direction of the company.

-

Third, a mission is only worthwhile if it is actually lived and practiced by the company. A good test is to see if a company’s regular employees actually know its mission and use it to guide their daily work.

Vision

In addition to missions, some companies also articulate a vision – a short aspirational statement about the future direction and impact of the company.

Unlike a mission, however, companies may eventually achieve and/or abandon their initial vision, and move on to a new one.

Strategic thinkers Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad coined the term “strategic intent” to describe a special kind of stretch vision accompanied by a strategic plan. A strategic intent goes beyond just a vision statement, galvanizing and inspiring employees, making the company expand its capabilities to achieve that vision.

Canon’s plan to “beat Xerox” is cited a good example of a strategic intent.

Values

Some companies also have a set of values that they declare they hold and will stick to.

These values can be seen as a “code of conduct” for the company and its employees. A company’s declared values essentially says to everyone – this is how we will behave as a company, and if you are an employee it is also how we expect you to behave.

Value Proposition, Activities, Realisation of Value and Scope

The VARS framework can be used to model a business along the following dimensions:

- Value Proposition: how the new business model is creating Economic Value Added (EVA) compared to existing ones.

- EVA is a technical term that refers to the difference between the value or utility that consumers obtain (or perceive) from a product or service. And the cost incurred to provide that same product or service;

- Activities, Resources and Capabilities: key enablers that the firm utilises to produce value;

- Realisation of value: how will the business make a profit while delivering its EVA?

- Scope of enterprise: the footprint of what the business does, and can be mainly envisioned along three key dimensions:

- Customer Segments: what categories of customers does the company serve?

- Horizontal: how many products does the company offer?

- Vertical: what activities are key capabilities vs outsourced?

External Modelling

External modelling aims at modelling the environment the environment and industry a firm operates in.

Macro Environment Analysis

The PESTEL framework can be used to systematically analyse the macro-environment a business operates in to create a more complete and robust evaluation of the trends the company faces.

The dimensions are:

- Political: local, state, national and regional policy; stability, security, corruption;

- Economic: growth, employment, inflation, interest and exchange rates, economic inequality;

- Socio-cultural: demographic trends, values and cultures, aspirations and expectations;

- Technological: Trends in R & D and innovation, process and operational innovation

- Ecological: pollution, waste and recycling, climate change;

- Legal: Courts, antitrust, labour, liability, international treaties and laws.

Industry Analysis

An industry is a set of similar firms associated with a single product-market. It’s important to notice that “industry” is a nested concept, and the definition can be very broad or narrow; e.g. for McDonald, industry can be food industry vs fast-food chains vs burger & coke shops.

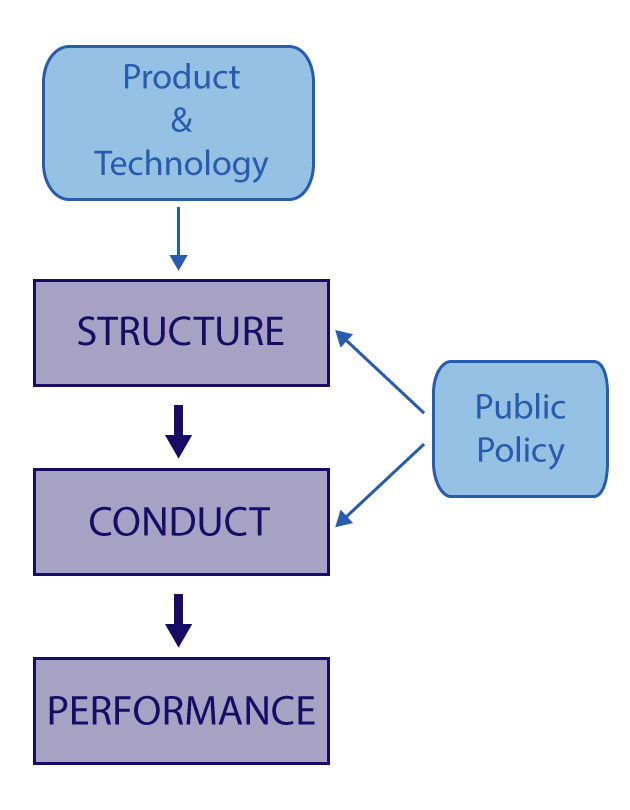

Structure, Conduct and Performance Paradigm

To analyse the performance of an industry we can use the Structure, Conduct and Performance paradigm (SCP), an analytical framework, to make relations amongst industry structure, industry conduct and industry performance.

The SCP paradigm is considered a pillar of industrial organization theory, and it has been since its conception a starting point when analysing markets and industries, not only in Economics, but also in the fields of business management and controlling.

Following its reasoning, an industry performance (which could be considered as the potential benefits to consumers and society as a whole) are determined by the conduct of the firms within the boundaries of this industry, which in turn depend on the structure of the market.

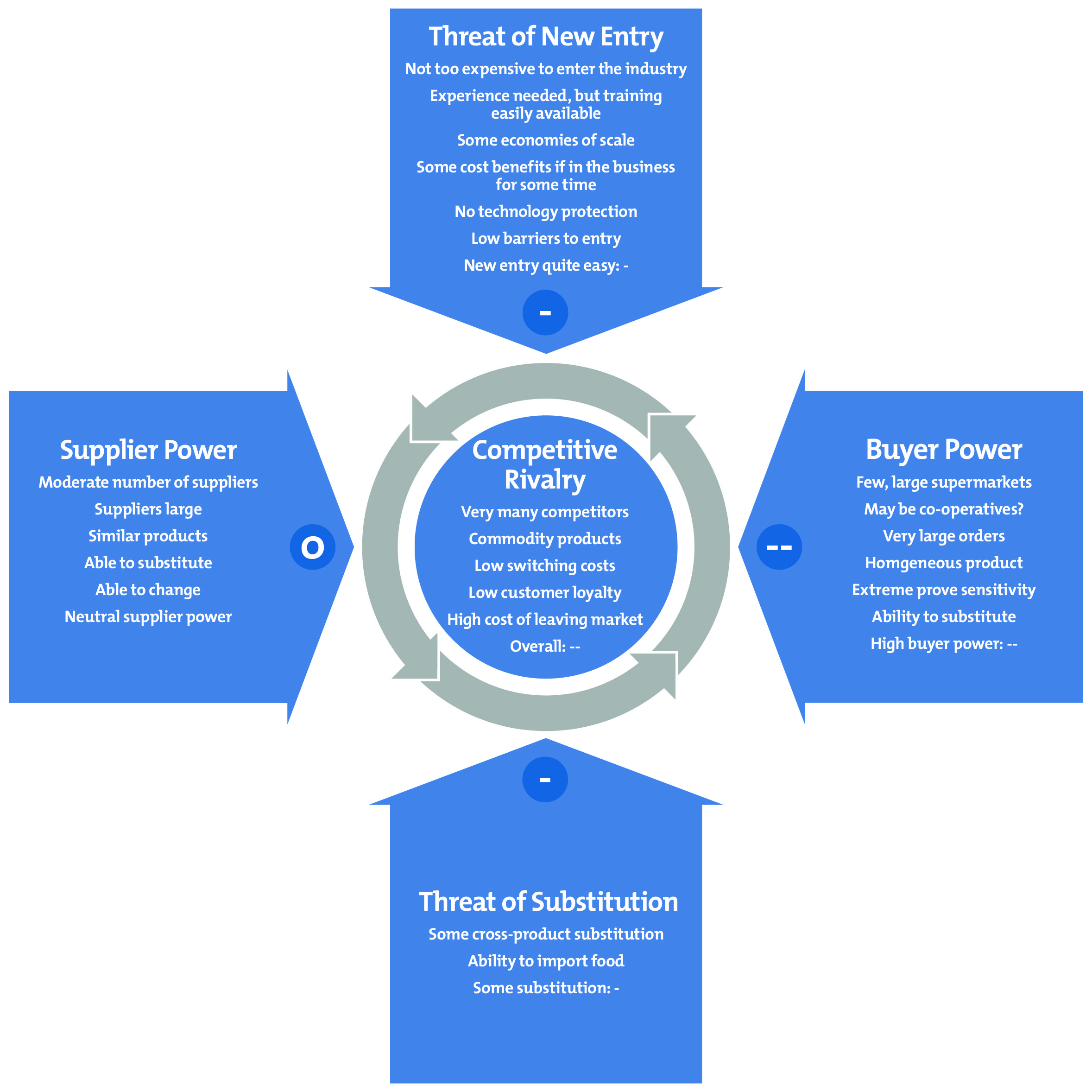

Industry Forces Model

Building on the SCP paradigm, the Forces Model can help us evaluate systematically the structure of an industry, which can then be used to model the conduct of its firms, and by that its profitability.

The model is usually represented graphically:

1. Threats of new entry

Is it easy for new entrants to develop cost-competitive production base, what entry barriers does the industry have?

- Natural entry barriers:

- Supply-side advantages (must be consistent to be real differentiators):

- Scale economies: costs decline with scale production;

- Scope economies: costs decline when multiple products are made;

- Learning curve economies: costs decline with total cumulative production;

- Capital requirements: large initial investment required;

- Demand-side advantages:

- Product differentiation: Customers are loyal to existing products & brands;

- Access to distribution channels: limited shelf space or difficult logistics

- Reproducibility advantages:

- Difficult to imitate technologies and processes

- Government regulations make it costly to enter

- Privileged access to raw materials

- Favourable location

- Strategic advantages:

- Stronger firms with reputation for retaliation (e.g. aggressive pricing, new products, etc), resources and excess capacity

- Supply-side advantages (must be consistent to be real differentiators):

2. Competitive rivalry

When firms can only compete on price, it can trigger a race to the bottom and lower profits for all firms; barriers to price rivalry are:

- Industry concentration: extent to which production / sale is in the hands of a small number of firms;

- Product differentiation: heterogeneous preferences amongst consumers for different products;

- Low Fixed / Storage Cost: items can be stored for later usage, without impacting a cost (e.g. drinks vs airline seats)

- Demand growth: firms can grow sales without eating each other’s market share;

- Low exit barriers: firms exit the industry rather than stay and fight at a loss.

3. Threat of Substitution

This force constraints the prices of an industry when similar / better / cheaper products could enter the market.

4. Buyer power

This force lowers the bargaining power of the industry when the industry relies on the buyers, and not vice-versa; buyers have more power when:

- They can switch from one product to another, without impact

- They are concentrated and price sensitive

5. Supplier power

This force lowers the bargaining power of the industry when the industry relies on the suppliers, and not vice-versa; suppliers have more power when:

- Suppliers are concentrated;

- Few substitute products with high integration;

- Product is important for the industry.

6. Complements power

Complements from a different industry act as a conceptual opposite of substitute: an industry can increase with low-cost high-quality complements.

Business Modelling - Step by Step

- Define the industry clearly

- Don’t be too broad or too narrow

- Evaluate the forces impacting the industry structure, one at the time

- Define both actors and structural attributes of the industry

- Don’t use one force to explain another

- Combine forces to understand overall profitability

- Profitability in an industry is limited by its weakest force, not the average of the forces

- Examine dynamics and trends that could change the industry

- Focus on long term profitability

- Gain insights into changes to the structure with PESTEL

- Examine implications for the company’s strategy

- Managerial action can mitigate and manipulate in its favour the forces

Analysing Competitive Advantage

Quite simply, a firm has a competitive advantage if it is able to outperform its competition, defined as the average performance of the rivals in the same industry.

Generally, because we are interested in for-profit firms, it makes sense that we would be interested in long run profit performance, calculated through the Economic Value Added metric, defined as the difference between the value generated and costs incurred by the company for the average customer.

While performance measured as economic value added (EVA) goes directly to the crux of whether or not a company has competitive advantage, a major challenge is that it is often difficult in practice to measure exactly how much value is being created for consumers by the company’s products. What is observable is price, and that is one indicator, albeit an imperfect one.

The general advice here is to know that EVA is what you need to focus on – at least conceptually – if you’re interested in competitive advantage. But also recognize that each of these approaches to measuring performance have advantages and drawbacks.

It is better to triangulate by using different approaches and develop a holistic perspective of how a company is faring, rather than put too much store by a single imperfect measure.

Sources of Competitive Advantage

When thinking about why companies might outperform their competitors, three conceptual points of view have been developed over time.

- The first approach, developed primarily by Michael Porter, treats activities as the focus of analysis.

- What differentiates one firm from another, then, is the set of activities that it chooses to undertake, activities it chooses not to undertake, how it executes each activity so that it is more (or less) effective, and ultimately how the activities are linked up and their synergies are exploited.

- In the second approach, the focus is on resources, by which we mean productive firm-specific assets of different kinds that one firm owns and another doesn’t.

- Thus, a well-known brand name is a resource, or knowhow for improving production processes, or real estate, or even cash is a resource.

- The third conceptual lens emphasizes capabilities – things that are relevant for the firm’s performance that it is very good at doing.

- Say, something like great customer service or innovative product design or low cost inventory management. Again, if a firm has unique capabilities that other firms don’t, then this will set it apart from its competitors

Sustained Competitive Advantage

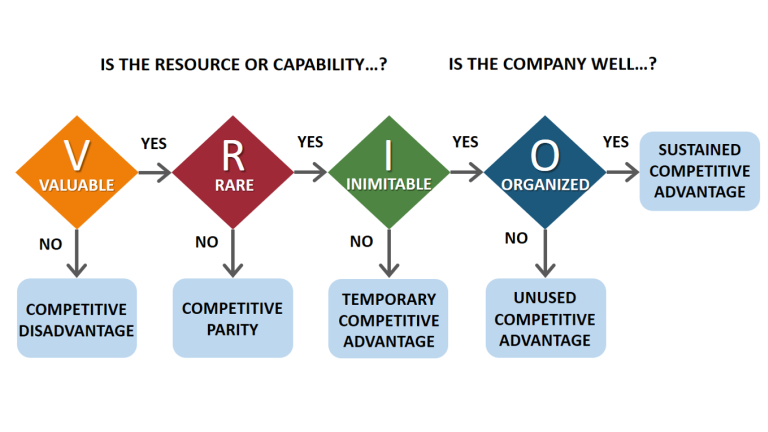

An important goal of strategic management is to create a competitive advantage for a company that is sustained over time. Conceptually, we can see the problem of sustaining a competitive advantage as one of overcoming four potential challenges.

The first two challenges are threats to the rarity of the firm’s internal attributes:

- Imitation: the threat that other firms will figure out and implement the company’s product development processes and routines;

- Replication: where other firms use different product development processes but achieve similar results.

To sustain a competitive advantage, firms need their internal attributes like their activity sets, resources and capabilities to be durable and not degrade or erode.

Much of the academic literature on sustained competitive advantage focuses on so called isolating mechanisms, which are barriers to the imitation and replication of a firm’s competitive advantage.

Some prominent examples of such isolating mechanisms include:

- Causal ambiguity: it’s unclear where exactly a company’s performance advantages come from;

- Complexity: implies that even if the individual elements of a company’s success are known, these elements can be combined in very many different ways, and success depends on a very precise combination;

- Tacit knowledge: knowledge that is tacit – as opposed to explicit or codified – is knowledge that cannot be easily explained and transferred to another;

- Time compression diseconomies: the quicker a firm develops the resource, the higher the development cost, making resource development more difficult and costly;

- Property rights: rights over resources in particular can be an effective barrier to imitation and replication.

In order for companies to transform these resources into sustainable competitive advantage, resources must have four attributes that can be summarized into the VRIO framework.

Valuable (VRIO)

First and foremost resources must be valuable. According to the RBV, resources are seen as valuable when they enable a firm to implement strategies that improve a firm’s efficiency and effectiveness by exploiting opportunities or by mitigating threats.

Rare (VRIO)

Secondly, resources must be rare. Resources that can only be acquired by one or few companies are considered to be rare. If a certain valuable resource is possessed by a large amount of players in the industry, each of the players has a capability to exploit the resource in the same way, thereby implementing a common strategy that gives non of the players a competitive advantage.

Inimitable (VRIO)

Although valuable and rare resources may help companies to engage in strategies that other firms cannot pursue since the other firms lack the relevant resources, it is no garantuee for long-term competitive advantage.

Organization-wide supported (VRIO)

The resources themself do not create any advantage for a company if the company is not organized in way to adequately exploit these resources and capture the value from them. The focal company therefore needs the capability to assemble and coordinate resources effectively. Examples of these organizational components include a company’s formal reporting structure, strategic planning and budgeting systems, management control systems and compensation policies.

Business Strategies

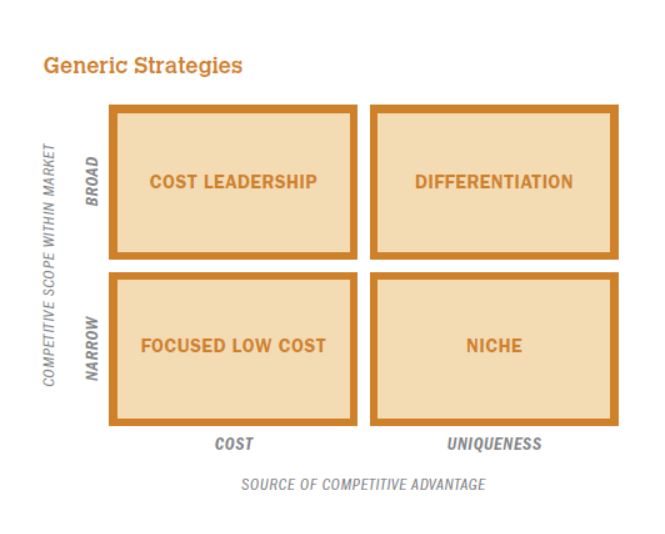

Generic Strategies

Cost Leadership (Similar Product at Lower Cost)

This approach keeps the value perceived by the customer the same, while lowering the cost incurred by the firm while delivering the product;

Main drivers of Cost Advantage are:

- Scale / Scope economies: Specialization, Large batch sizes, Indivisible costs, Common inputs

- Input Costs: Raw material sources, Location, Supplier relationships/bargaining

- Production Techniques: Automation, Total Quality Management, Reducing Waste

- Product Design: Design variety and complexity, Design for manufacturing, Efficient materials use

- Capacity Utilization: Amortization of high fixed cost assets, Filling spare capacity

- Organizational or managerial inefficiency: Slow decision making, Inertia, Bureaucracy, Hierarchy, Politics

Differentiation Advantage (Price Premium from Unique Product)

This approach increases the value, while keeping the cost the same.

Main drivers of Differentiation Advantage are:

- Identifying customers’ value drivers

- Market research & company insights

- Common value drivers

- Product features

- Customer service

- Customization

- Complements

- Delivering value

- Activities, resources, capabilities

Narrow vs Broad Focus

In addition to the cost-differentiation distinction, generic strategies can also be applied with broad scope – for example to most customer segments and sales channels – or with narrow scope – only to specific segments and/or channels.

The resulting combinations create four possible generic strategies – broad cost leadership and broad differentiation, and narrow low cost leadership and narrow differentiation.

So what purpose is served by limiting scope when pursuing a cost or differentiation based strategic positioning?

-

Narrow scope and differentiation: These two seem like natural fit, by being more focused helps promote the aura of exclusivity around the product, making them more valuable to customers. Additionally, being narrow in channel scope might also help to contain costs because the volumes in which these products could be sold at non-luxury retailers may too small to justify the logistics, inventory and potential unsold stock.

-

Narrow scope and cost leaderships: While we often think scale as being helpful to reduce cost, some businesses may not have significant scale economies to begin with. Moreover, it may actually be possible to reduce costs by avoiding some customer segments that are too costly to serve.

Dual Strategies

Dual strategies try to increase the perceived value, while lowering cost. They are much more difficult because creating differentiation works against reducing costs, and vice versa.

Due to these fundamental forces working against each other, dual strategies can become incoherent, leading to a “Stuck in the middle” problem and ultimately to competitive disadvantage.

For the Dual advantage strategy to be feasible two things are needed:

- Managerial driven innovation;

- Disciplined evaluation of cost-differentiation trade-offs.

Strategic Renewal

As time goes, things can change and a company can lose its strategic alignment. When this happens, dynamic capabilities, enabling a company to change resources or capabilities, become extremely valuable.

Dynamic Capabilities

Dynamic capabilities are higher order or secondary capabilities that help companies change how they survive and perform

These capabilities can contrast with operational capabilities, which essentially help the firm with current performance.

Some types of capabilities that can be thought of as dynamic are those related to acquisitions, alliances, new product development, business development, or organizational transformation.

3-P Dynamic Capabilities Framework

The 3-P dynamic capabilities framework can a company plan its strategic renewal.

The 3-Ps refer to Processes, Positions and Paths that can be deployed effectively in pursuit of a new strategy:

- Processes: Well-developed activities and routines encoded within the firm;

- Positions: Resource owned or available;

- Paths: Opportunities / options that lie ahead the firm.

The application of 3-P framework relies significantly on the skill and judgment of those applying it. Nonetheless, it is valuable to have some way of addressing such an important question like strategic renewal than none at all.

Related

Other Peopleware Pages

- July 16, 2019: Organisational Culture

- June 22, 2019: Highly Effective Managers

- June 10, 2019: Organisational Design

- January 06, 2019: Performance Management

- January 06, 2019: Decision Making

- October 11, 2018: Psychological Safety

- October 10, 2018: Radical Candor

- October 10, 2018: Objectives and Key Results